By Ishmael Bishop

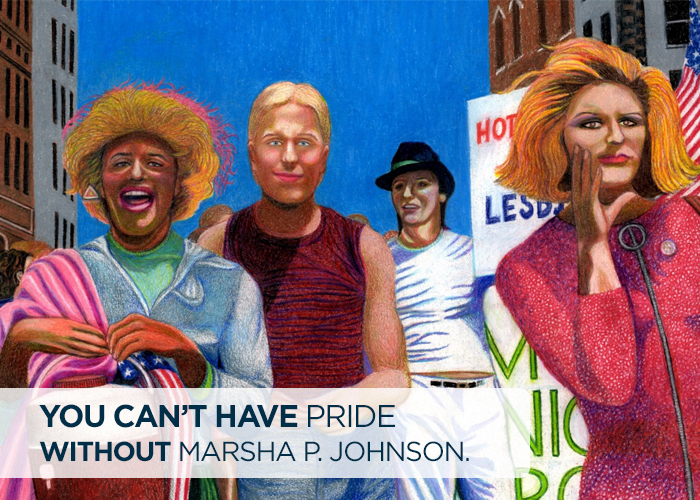

Since its origin in the late 1960s, Pride has referenced a coalition of grassroots organizers, community members, activists, performers, sex workers, and gender and sexual subversives who come together to celebrate the diversity within the LGBTQ+ community. Marsha P. Johnson was an architect to some of the earliest iterations of Pride and because of her resilience in the face of bigotry and discrimination, Pride lives to this day.

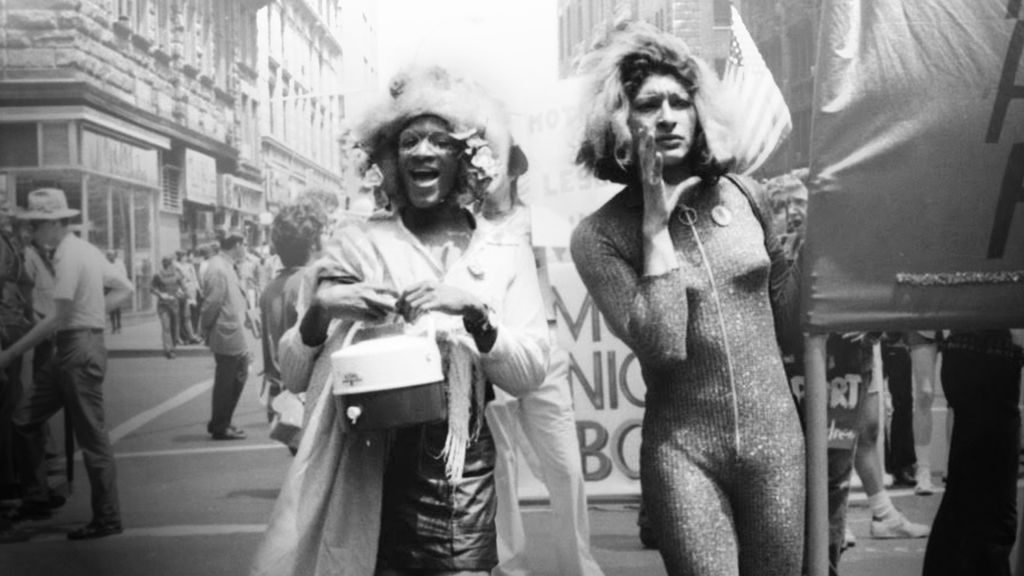

The original Pride was a riot incited outside the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village in New York City in 1969. Some historians consider the Stonewall Riot the spark to the modern LGBTQ rights movement. Others uphold Stonewall as a symbol of resistance to the social and political discrimination faced by the LGBTQ community and effectuated by the police.

While Pride proclaims itself to be many things to many people – including the harbinger of inclusion and civil rights in this country – Pride continues to provoke contradictions within those who have historically remained on the margins.

In 2015, a dramatic reproduction of the 1969 New York City rebellion titled Stonewall, directed by Roland Emmerich, was heavily criticized in the media for whitewashing history. Several online writers pointed to the film’s numerous erasures and its predominantly white cast as epic failures. In particular, protagonist Danny Winters (played by Jeremy Irvine) reflected the embodiment of white, cisgender queer politics – the exact antithesis of Marsha P. Johnson, who many allege threw the brick that sparked the riot.

In 2017, the Netflix documentary, The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson by David France, attempted to also recount the story of Johnson including her frontline participation in the original Stonewall riot. Following its debut, however, the documentary came under fire when France was accused of stealing research from activist, filmmaker, and writer Reina Gossett. In an op-ed, Gossett, a black transwoman and co-director of the film Happy Birthday Marsha!, takes particular issue with the lack of resources available to transwomen of color to create projects that celebrate members of their communities.

Gossett superbly highlights the contradiction between visibility, a long touted benefit of Pride, and the intensifying violence against trans people. She writes,

“It is more important now more than ever for trans and gender nonconforming people to be the architects of our own narratives. While trans visibility is at an all-time high, with trans people increasingly represented in popular culture, violence against us has also never been higher. The push for visibility without it being tied to a demand for our basic needs being met often leaves us without material resources or tangible support, and exposed to more violence and isolation.”

As Pride draws near, it is crucial that we learn and understand our history through the eyes of those who have struggled through it.

Johnson, a revolutionary black transwoman, sex worker, and drag queen, was often overlooked and cast out of mainstream LGBTQ organizing because of her gender identity, race, HIV+ status, and occupation. During her lifetime, Johnson suffered many abuses in both her personal and professional lives, all of which can be linked to her position as a black transwoman. What is even more unfortunate is that Johnson’s untimely death at 46 years of age remains unsolved, illustrating how the mainstream LGBTQ movement prioritizes some, in fact, defines itself by the death of a select handful, but certainly not all.

Johnson’s work toward liberation is well documented.

Following the events at Stonewall, Johnson joined the Gay Liberation Front with friend Sylvia Rivera. The GLF made it their mission to to improve the material conditions for LGBTQ citizens by eradicating homophobic laws and city ordinances. A 1970s newspaper titled Come Out stated that, “the Gay Liberation Front welcomes any gay person, regardless of sex, race, age or social behavior. Though some other gay organizations may be embarrassed by drags or transvestites, GLF believes that we should accept all of our brothers and sisters unconditionally”. Under this banner, Johnson and Rivera found a home.

In June of 1970, the first of the GLF marches took place in New York City. These marches, ones that Rivera and Johnson had hands in organizing, would develop exponentially and become what we in 2018 call Pride. That same year, Johnson and Rivera formed the Street Transvestite (now Transgender) Action Revolutionaries (STAR), a community organization that provided services to homeless LGBTQ youth in select U.S. cities and England. In the 1980s, Johnson became an outspoken activist with the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) with whom she protested on Wall Street against the inaccessibility of new HIV/AIDS medication.

Marsha P. Johnson’s engagement in the earliest iterations of Pride, and yet her struggle to sustain housing and mental health care, astutely demonstrates the contradiction inherent to participating in a movement that is ignorant of your humanity.

What is important to realize is that Johnson’s work transcended race, class, and gender in ways that the larger and whiter LGBTQ movement continues to not.

Gossett remarks,

“So much of what Marsha had to deal with remains a reality for many of us. Marsha’s history has helped me make plain the connections between the historical erasure of trans women of color from the LGBT movement, and contemporary forms of anti-black transphobic violence happening today.”

The Pride of Johnson’s era was a protest that sought to mitigate the woeful conditions that impacted New York City’s most vulnerable. Pride, at the time, was an opportunity to vociferously advocate on behalf of those who were most directly harmed by state power, the police, and the wider anti-LGBTQ infrastructure.

In the early 1990s, Pride began to coalesce into more or less what is today – primarily a celebratory event equipped with corporate sponsorships, concerts, party venues, and speed dating. Nevertheless, Pride remains a fertile site to demand political action. In 2017, the group “No Justice No Pride” – a collective of activists based in the Washington, DC who exist to “end the LGBT movement’s complicity with systems of oppression,” including the DC Metropolitan and New York City police departments – announced their public demands during the Capital Pride parade by halting festivities for approximately 90 minutes.

“We deserve to celebrate Pride without being forced alongside the Police who kill us,” said Angela Peoples, one of the participants in a No Justice No Pride statement. “Pride should be a haven for the entire LGBTQ community. The Capital Pride Board has shown who it’s prioritizing. No Justice No Pride is for everyone who has previously been excluded and for a different vision of what this event could and should be.” The “haven” that Peoples alludes to is shattered by the “Police who kill us,” an observation that keenly emphasizes the contradiction of Pride – contradictions that Johnson and her comrades were likely to have experienced on a daily basis.

Pride is a time to appreciate how far we have come as a community out of a place of abject cruelty and adversity to where we are now.

Clearly, there is still much to accomplish in the fight for equality and anti-discrimination. As Micah Bazant writes, “No pride for some of us without liberation for all of us,” which eloquently encapsulates the persistence of Johnson’s activism. Her life’s work teaches me that it is meaningless to take pride in shallow wins that improve the lives of some while so many others continue to suffer in silence.

Pride is not squarely an event for gay, cisgender, white men and women to enjoy and feel comfortable participating in. Rather, Pride is a rebirth of political energy. Marsha P. Johnson’s riveting model is one that I plan to follow during the upcoming month of Pride – one that I reckon you might as well.

“No pride for some of us without liberation for all of us.”

Ishmael Bishop is a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He identifies as a black queer writer and editor who’s written for Mask and Scalawag magazines. More of his work can be read here. Contact Ishmael here.

This post was originally published on Th-Ink Queerly.